👋 Note: Originally published on Feb 12, 2018 on Medium.

For ethereum 2018 is the year of infrastructure. This is the year when early adoption will test the limits of the network, renewing focus on technologies built to scale ethereum.

Ethereum is still in its infancy. Today, it isn’t safe or scalable. This is well understood by anyone who works closely with the technology. But over the last year, the ICO-driven hype has begun to far exaggerate the current capabilities of the network. The promise of ethereum and web3 — a safe, easy to use decentralized internet, bound by a common set of economic protocols, and used by billions of people — is still on the horizon, and will not be realized until critical infrastructure is built.

The projects working to build this infrastructure and expand the capabilities of ethereum are commonly referred to as scaling solutions. These take many different forms, and are often compatible or complimentary with each other.

In this long post I want to dive deep into one category of scaling solution: “off-chain” or “layer 2” solutions.

- First, we’ll discuss the scaling challenges of ethereum (and all public blockchains) in general.

- Second, we’ll cover the different approaches to solving the scaling challenge, distinguishing between “layer 1” and “layer 2” solutions.

- Third, we’ll delve into layer 2 solutions and explain how they work — specifically, we’ll talk about state channels, Plasma, and Truebit

This article focuses on giving the reader a thorough and detailed conceptual understanding of how layer 2 solutions work. But we won’t dig into code or specific implementations. Rather, we focus on understanding the economic mechanisms used to build these systems, and the common insights that are shared between all layer 2 technologies.

1. The scaling challenges of public blockchains

First, it’s important to understand that “scaling” isn’t a single, specific problem. It refers to a collection of challenges that must be overcome to make ethereum useful to a global user base of billions of people.

The most commonly discussed scaling challenge is transaction throughput. Currently, ethereum can process roughly 15 transactions per second, while in comparison Visa processes approximately 45,000/tps. In the last year, some applications — like Cryptokitties, or the occasional ICO — have been popular enough to “slow down” the network and raise gas prices.

The core limitation is that public blockchains like ethereum require every transaction to be processed by every single node in the network. Every operation that takes place on the ethereum blockchain — a payment, the birth of a Cryptokitty, deployment of a new ERC20 contract — must be performed by every single node in the network in parallel. This is by design — it’s part of what makes public blockchains authoritative. Nodes don’t have to rely on someone else to tell them what the current state of the blockchain is — they figure it out for themselves.

This puts a fundamental limit on ethereum’s transaction throughput: it cannot be higher than what we are willing to require from an individual node.

We could ask every individual node to do more work. If we doubled the block size (i.e., the block gas limit), it would mean that each node is doing roughly double the amount of work processing each block. But this comes at the cost of decentralization: requiring more work from nodes means that less powerful computers (like consumer devices) may drop out of the network, and mining becomes more centralized in powerful node operators.

Instead, we need a way for blockchains to do more useful stuff without increasing the workload on individual nodes.

Conceptually, there are two ways we might go about solving this problem:

I. What if each node didn’t have to process every operation in parallel?

The first approach rejects our premise — what if we could build a blockchain where every node didn’t have to process every operation? What if, instead, the network was divided into two sections, which could operate semi-independently?

Section A could process one batch of transactions, while Section B processed another batch. This would effectively double the transaction throughput of a blockchain, since our limit is now what can be processed by two nodes at the same time. If we can split a blockchain into many different sections, then we can increase the throughput of a blockchain by many multiples.

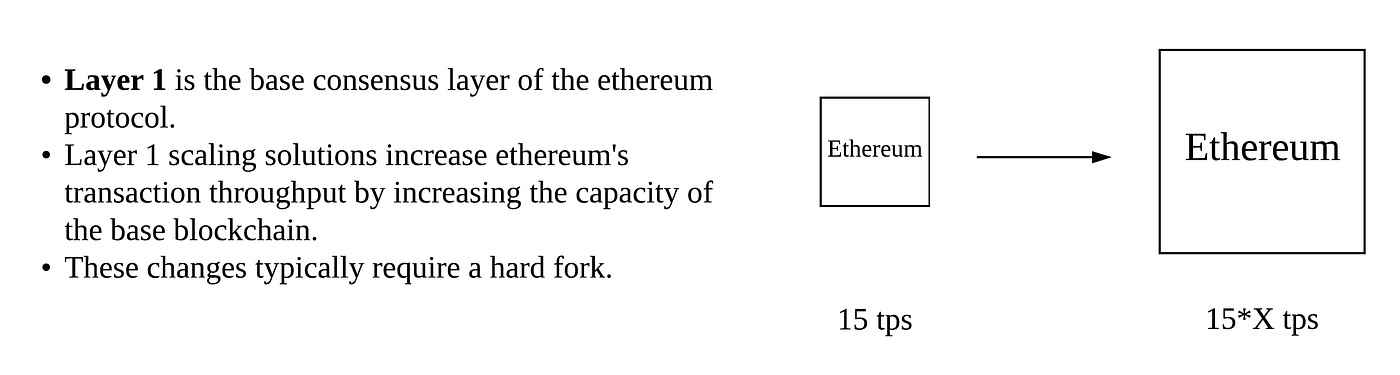

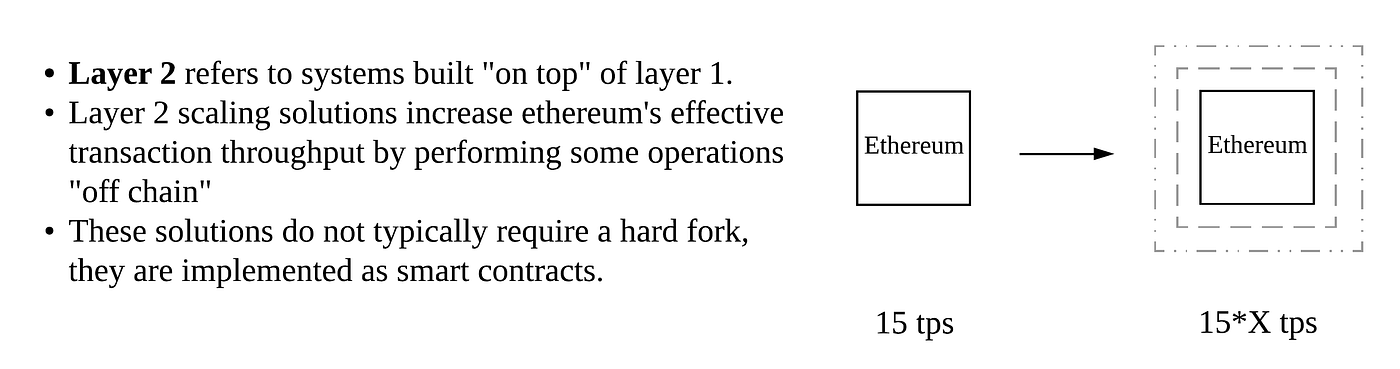

This is the insight behind “sharding”, a scaling solution being pursued by Vitalik’s Ethereum Research group and others. A blockchain is split into different sections called shards, each of which can independently process transactions. Sharding is often referred to as a Layer 1 scaling solution because it is implemented at the base-level protocol of ethereum itself. If you want to learn more about sharding, I recommend this extensive FAQ and this blog post.

II. What if we could squeeze more useful operations out of ethereum’s existing capacity?

The second option goes in the opposite direction: rather than increase the capacity of the ethereum blockchain itself, what if we could do more things **with the capacity we already have? **The throughput of the base-layer ethereum blockchain would be the same, but in practice we would be able to do many more operations that are useful to people and applications — like transactions, state updates in a game, or simple computations.

This is the insight behind “off-chain” technologies like state channels, Plasma, and Truebit. While each of these is solving a different problem, they all function by performing operations “off chain” instead of on the ethereum blockchain, while still guaranteeing a sufficient level of security and finality.

These are also known as Layer 2 solutions because they are built “on top of” the ethereum main-chain. They do not require changes to the base level protocol — rather, they exist simply as smart contracts on ethereum that interact with off-chain software.

2. Layer 2 solutions are cryptoeconomic solutions

Before diving into specific layer 2 solutions, it’s important to understand the underlying insight that makes them possible.

The basic power of a public blockchain is in cryptoeconomic consensus. By carefully aligning incentives and securing them with software & cryptography, we can create networks of computers that reliably come to agreement about the internal state of a system. This is the key insight of Satoshi’s whitepaper, which has now been applied in the design of many different public blockchains including bitcoin and ethereum.

Cryptoeconomic consensus gives us a core hard kernel of certainty — unless something extreme like a 51% attack happens, we know that on-chain operations — like payments, or smart-contracts — will execute as written.

The insight behind layer 2 solutions is that we can use this core kernel of certainty as an anchor — a fixed point to which we attach additional economic mechanisms. This second layer of economic mechanisms can extend the utility of public blockchains outwards, letting us have interactions off of the blockchain that can still reliably refer back to that core kernel if necessary.

These layers built “on top” of ethereum won’t always have the same guarantee as on-chain operations. But they can still be sufficiently final and secure to be very useful — especially when that slight decrease in finality lets us perform operations much faster or with lower overhead costs.

Cryptoeconomics didn’t begin and end with Satoshi’s whitepaper — it’s a body of techniques that we are only learning to apply. Not just in the design of core protocols, but in the design of second layer systems that extend the functionality of the underlying blockchain.

I. State channels

State channels are a technique for performing transactions and other state updates “off chain”. However, things that happen “inside” of a state channel still retain a very high degree of security and finality: if anything goes wrong, we still have the option of referring back to the “hard kernel” of certainty found in on-chain transactions.

Most readers will be familiar with the idea of a payment channel, which has been around for several years, and recently implemented on bitcoin through the lightning network. State channels are the more general form of payment channels — they can be used not only for payments, but for any arbitrary “state update” on a blockchain — like changes inside a smart contract. State channels were first described in detail by Jeff Coleman in 2015.

The best way to explain how a state channel works is by looking at an example. Keep in mind that this is a conceptual explanation, meaning that we won’t get into the technical details of a specific implementation.

Imagine that Alice and Bob want to play a game of tic tac toe, where the winner receives 1 eth. The naive way to do this would be to create a smart contract on ethereum that implements the rules of tic tac toe and keeps track of each players’ moves. Every time a player wants to make a move, they send a transaction to the contract. When one player wins, as determined by the rules, the contract pays out the 1 eth to the winner.

This works, but is inefficient and slow. Alice and Bob are having the entire ethereum network process their game, which might be overkill for what they need. They have to pay gas costs every time a player wants to make a move, and they have to wait for blocks to be mined before making the next move.

Instead, we can design a system that lets Alice and Bob play tic-tac-toe with as few on-chain operations as possible. Alice and Bob will be able to update the state of the game off-chain, while still having full confidence that they can revert back to the ethereum main-chain if necessary. We call this system a “state channel”.

First, we create a smart contract “Judge” on the ethereum main-chain that understands the rules of tic-tac-toe, and can identify Alice and Bob as the two players in our game. This contract holds the 1 eth prize.

Then, Alice and Bob begin playing the game. Alice creates and signs a transaction describing her first move, and sends it to Bob, who also signs it, sends back the signed version, and keeps a copy for himself. Then Bob creates and signs a transaction describing his first move, and sends it to Alice, who also signs it, sends it back, and keeps a copy. Each time, they are updating the current state of the game between them. Each transaction contains a “nonce”, which simply means that we can always tell later in what order the moves happened.

So far, none of this is happening on-chain. Alice and Bob are simply sending transactions to each other over the internet, but nothing is hitting the blockchain yet. However, all of the transactions could be sent to the Judge contract — in other words, they are valid ethereum transactions. You can picture this as two people writing a series of blockchain-certified cheques back and forth to each other. No money has actually been deposited or withdrawn from a bank, but each has a stack of cheques that they could deposit whenever they want.

When Alice and Bob are done playing the game — perhaps because Alice has won — they can close the channel by submitting the final state (e.g. a list of transactions) to the Judge contract, paying only a single transaction fee. The Judge ensures that this “final state” is signed by both parties, and waits a period of time to ensure that no one can legitimately challenge the result, and then pays out the 1 eth award to Alice.

Why do we need this “challenge period” where the Judge contract waits?

Imagine that instead of sending the real final state to the Judge, Bob sent an old version of the state — one where he was winning ahead of Alice. The Judge is just a dumb contract — on its own, it has no way of knowing whether this is the most recent state or not.

The challenge period gives Alice a chance to prove to the Judge contract that Bob has lied about the final state of the game. If there is a more recent state, then she will have a copy of the signed transactions, and she can submit those to the Judge. The Judge can tell that Alice’s version is more recent by checking the nonce, and Bob’s attempt to steal the win is rejected.

Features and limitations

State channels are useful in many applications, where they are a strict improvement over doing operations on-chain. However, it’s important to keep in mind the particular tradeoffs that have been made when deciding whether an application is suitable for being channelized:

- State channels rely on availability. If Alice lost her internet connection during a challenge (maybe because Bob, desperate to claim the prize, sabotaged her home’s internet connection) she might not be able to respond before the challenge period ends. However, Alice can pay someone else to keep a copy of her state and maintain availability on her behalf.

- They’re particularly useful where participants are going to be exchanging many state updates over a long period of time. This is because there is an initial cost to creating a channel in deploying the Judge contract. But once it is deployed, the cost per state update inside that channel is extremely low.

- State channels are best used for applications with a defined set of participants. This is because the Judge contract must always know the entities (i.e. addresses) that are part of a given channel. We can add and remove people, but it requires a change to the contract each time.

- State channels have strong privacy properties, because everything is happening “inside” a channel between participants, rather than broadcast publicly and recorded on-chain. Only the opening and closing transactions must be public.

- State channels have instant finality, meaning that as soon as both parties sign a state update, it can be considered final. Both parties have a very high guarantee that, if necessary, they can “enforce” that state on-chain.

At L4, we’re building Counterfactual: a framework for generalized state channels on ethereum. Our general purpose, modular implementation will let developers use state channels in their application without needing to be state channel experts themselves. You can read more about the project here. We’ll be releasing a paper describing our technique in Q1 2018.

The other notable state channels project for ethereum is Raiden, which is currently focused on building a network of payment channels, using a similar paradigm as the lightning network. This means that rather than have to open up a channel with the specific person(s) you want to transact with, you can open up a single channel with an entity connected to a much larger network of channels, enabling you to make payments to anyone else connected to the same network without additional fees.

In addition to Counterfactual and Raiden, there are several application-specific channel implementations on ethereum. For instance, Funfair has built state channels (which they call “Fate channels”) for their decentralized gambling platform, Spankchain has built one-way payment channels for adult performers (they also used a state channel for their ICO), and Horizon Games is using state channels in their first ethereum-based game.

II. Plasma

On August 11 2017, Vitalik Buterin and Joseph Poon released a paper titled Plasma: Autonomous Smart Contracts. The paper introduced a novel technique that could enable ethereum to reach many more transactions per second than currently possible.

Like state channels, Plasma is a technique for conducting off-chain transactions while relying on the underlying ethereum blockchain to ground its security. But Plasma takes the idea in a new direction, by allowing for the creation of “child” blockchains attached to the “main” ethereum blockchain. These child-chains can, in turn, spawn their own child-chains, who can spawn their own child-chains, and so on.

The result is that we can perform many complex operations at the child-chain level, running entire applications with many thousands of users, with only minimal interaction with the ethereum main-chain. A Plasma child-chain can move faster, and charge lower transaction fees, because operations on it do not need to be replicated across the entire ethereum blockchain.

In order to understand how Plasma works, let’s walk through an example of how it could be used.

Let’s imagine that you’re creating a trading-card game on ethereum. The cards will be ERC 721 non-fungible tokens (like Cryptokitties), but have certain features and attributes that lets users play against each other — like in Hearthstone, or Magic the Gathering. These kinds of complex operations are expensive to do on-chain, so you decide to use Plasma instead for your application.

First, we create a set of smart-contracts on ethereum main-chain that serve as the “Root” of our Plasma child-chain. The Plasma root contains the basic “state-transition rules” of our child chain (things like “transactions cannot spend assets that have already been spent”), records hashes of the child-chain’s state, and serves as a kind of “bridge” that lets users move assets between the ethereum main-chain and the child-chain.

Then, we create our child-chain. The child-chain can have its own consensus algorithm — in this example, let’s say that it uses Proof of Authority (PoA), a simple consensus mechanism that relies on trusted block producers (i.e. validators). Block producers are analogous to miners in a “Proof of Work” system — they are the nodes that receive transactions, form blocks, and collect transaction fees. Let’s keep our example simple, and say that you (the company that created the game) are the only entity that is creating blocks — i.e. your company runs a few nodes that are the block producers for our child-chain.

Once the child-chain is created and active, the block producers make periodic commitments to the root contract. This means they are effectively saying “I commit that the most recent block in the child-chain is X”. These commitments are recorded on-chain in the Plasma root as a proof of what has happened in the child-chain.

Now that the child-chain is ready, we can create the basic components of our trading card game. The cards themselves are ERC721’s, initially created on the ethereum main-chain, and then moved onto the child-chain through the plasma root. This introduces a crucial point: Plasma lets us scale interactions with blockchain-based digital assets, but those assets should be created first on the ethereum-main chain. Then, we deploy the actual game application smart-contracts on the child-chain, which contains all of the game logic and rules.

When a user wants to play our game, they are only interacting with the child chain. They can hold assets (the ERC721 cards), buy and trade them for ether, play rounds of the game against other users — whatever our game lets them do — without ever interacting directly with the main-chain. Because only a much smaller number of nodes (i.e. block producers) have to process transactions, fees can be much lower and operations can be faster.

But how can this be safe?

By moving more operations off the main-chain and onto a child-chain, it’s clear we can perform more operations. But how secure is it? Are transactions that happen on the child-chain actually considered final? After all, we’ve just described a system where a single entity controls the block production for our child chain. Isn’t that centralized? Can’t the company steal your funds or take your collectible cards whenever it wants?

The short answer is that even in a scenario where a single entity controls 100% of block production on a child chain, Plasma gives you a basic guarantee that you can always withdraw your funds and assets back onto the main chain. If a block producer starts acting maliciously, the worst that can happen is they force you to leave the child-chain.

Let’s walk through a few different ways block producers could behave badly, and see how Plasma deals with those scenarios.

First, imagine that a block producer tries to cheat you by lying — by creating a fake new block where suddenly your funds are controlled by them. They are the only block producer, so they’re free to introduce a new block that doesn’t actually follow the rules of our blockchain. Just like other blocks, they will have to publish a commitment to the Plasma root contract containing evidence of this block.

As mentioned above, the user always has an ultimate guarantee that they can withdraw their assets back to main-chain. In this scenario, the user (or rather an application acting on their behalf) would detect the attempted theft, and withdraw before the block producer can try and use the assets they’ve “stolen”.

Plasma also creates a mechanism to prevent fraud short of withdrawing to main-chain. Plasma includes a mechanism whereby anyone — including you — can publish a fraud proof to the root contract, to try and show that the block producer has cheated. This fraud proof would contain information about the previous block, and allows us to show that according to the state-transition rules of the child-chain, the false block doesn’t properly follow from the previous state. If fraud is proven, the child-chain is “rolled back” to the previous block. Even better, we construct a system where any block producer who signed off on the false block is penalized by losing an on-chain deposit.

plasma.io/plasma.pdf

But submitting a fraud proof requires having access to the underlying data — i.e. the actual history of blocks that are used to prove the fraud. What if the block producers are also not sharing information about previous blocks, to prevent Alice from being able to submit a fraud proof to the root contract?

In this case, the solution is for Alice to withdraw her funds and leave the child-chain. Essentially Alice submits a “Proof of Funds” to the root contract. After a delay period during which anyone can challenge her proof (e.g. to show she actually spent those funds in a later valid block), Alice’s funds are moved back to the ethereum main-chain.

Lastly, block producers can censor users of the child-chain. If they wanted, block producers could simply never include certain transactions in their blocks, effectively preventing a user from performing any operations on the child-chain. Once again, the solution is simply to withdraw all of our assets back onto the ethereum main-chain as above.

Withdrawals themselves pose risks, however. One concern is what would happen if everyone using a child-chain tried to withdraw at the same time. In the case of a mass withdrawal, there might not be enough capacity on the ethereum main-chain to process everyone’s transactions within the challenge period, meaning users could lose funds. Although there are many possible techniques for preventing this, e.g. by extending the challenge period in a way that is responsive to demand for withdrawals.

It’s worth noting that it doesn’t need to be the case that all block producers are controlled by one entity — this is simply the extreme case in our example. We can create child-chains whose block production is spread among many different entities — i.e. actually decentralized in a way that is more similar to public blockchains. In those cases, there is less risk that block producers would interfere in the way described above, and so less risk that a user would have to move their assets back to the ethereum main-chain.

Now that we’ve covered both state channels and Plasma, it’s worth noting a few points of comparison.

One difference is that state channels can perform instant withdrawals when all of the parties in the channel consent to the withdrawal. If Alice and Bob agree to close out a channel and withdraw their funds, so long as they both agree to the final state they can get their assets out of the channel immediately. This is not possible on Plasma, where users must always go through a withdrawal process that involves a challenge period, as described above.

State channels should also be less expensive per transaction than Plasma, and be faster. This means that we will likely build state channels on Plasma child-chains. For example, in an application where two users are exchanging a series of small transactions. Building a state channel at the child-chain level should be cheaper and faster than performing each of those transactions on the child-chain directly.

Finally, it’s worth noting that this is only a partial description that leaves out many details. Plasma itself is in very early stages. If you’re interested in learning more about current work on Plasma, check out Vitalik’s recent proposal for a “Minimal Viable plasma” (i.e. a stripped-down plasma implementation). There’s work being done by a group based in Taiwan, which you can find in this repo. OmiseGo is working on an implementation for their decentralized exchange — they posted a recent update about their progress here.

III. Truebit

Truebit is a technology to help ethereum conduct heavy or complex computation off-chain. This makes it different from state channels and Plasma, which are more useful for increasing the total transaction throughput of the ethereum blockchain. As we discussed in the opening section, scaling is a multi-faceted challenge that requires more than high transaction throughput. Truebit won’t let us do more transactions, but it will let ethereum based applications do more complex things in a way that can still be verified by the main-chain.

This will let us do operations useful to ethereum applications that are too computationally expensive to do on chain. For instance, validating Simple Payment Verification (SPV) proofs from other blockchains, which could let ethereum smart-contracts “check” whether a transaction has happened on another chain (like bitcoin or dogecoin).

Let’s walk through an example. Imagine that you have some expensive computation — like an SPV proof — that needs to be performed as part of an ethereum application. You can’t simply do it as part of a smart contract on ethereum main-chain, because SPV proofs are far too computationally expensive. Remember, it’s very costly to perform any computation on ethereum because every node must perform that operation in parallel. Blocks in ethereum have a maximum gas limit that sets a cap on how much computation can be done by all the transactions combined in that block. But an SPV proof is so computationally expensive that it would require many multiples of the entire gas limit for an individual block, even if it were the only transaction inside.

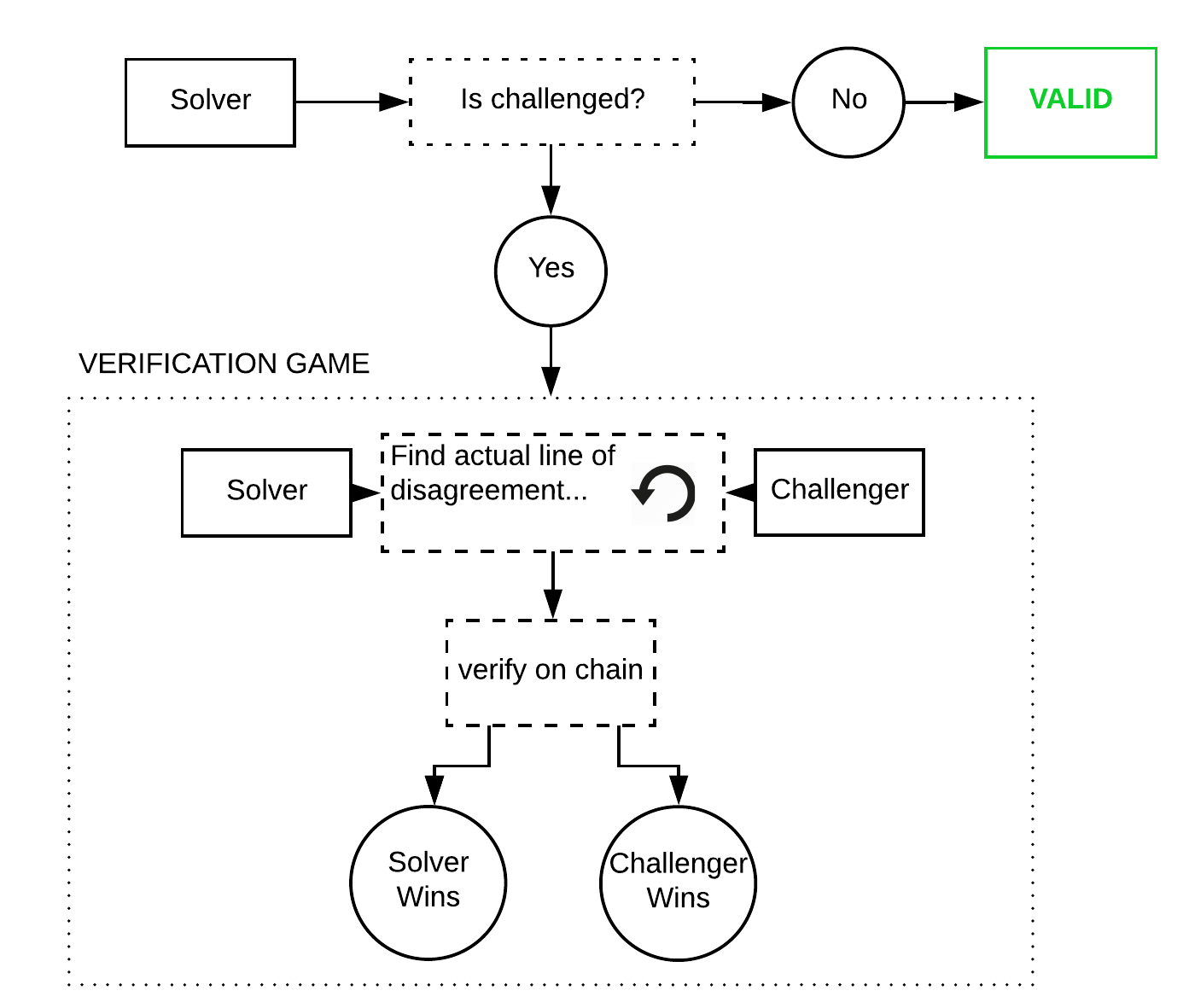

Instead, you pay someone else a small fee to do the computation off chain. The person you paid to do this is called a solver.

First, the solver pays a deposit held in a smart contract. Then, you give the solver a description of the computation they need to execute for you. They run the computation, and return the result. If the result is correct (more on that in a second), their deposit is returned. If it turns out that solver did not properly perform the computation — i.e. they cheated or made a mistake — they lose their deposit.

But how can we tell whether the result was correct, or false? Truebit uses an economic mechanism called the “verification game”. Essentially, we create an incentive for other parties called challengers to check the solvers’ work. If a challenger is able to prove through the verification game that a solver submitted a false result, then they collect a reward, while the solver loses their deposit.

Because the verification game is performed on-chain, it cannot simply compute the result (which would defeat the entire purpose of the system — if we could do the computation on-chain, we wouldn’t need Truebit). Rather, we force both the solver and challenger to identify the specific operation that they disagree about. In effect, we are backing both parties into a corner — finding the actual line of code where they disagree about the outcome.

Once that specific operation is identified, it’s small enough to actually be executed by the ethereum main-chain. We then execute that operation through a smart-contract on ethereum, which settles once and for all which party was telling the truth and which was lying or mistaken.

If you want to learn more about Truebit, you can read the paper here, or this blog post by Simon de la Rouviere.

Conclusion

Layer 2 solutions share a common insight: once we have the hard kernel of certainty provided by a public blockchain, we can use it as an anchor for cryptoeconomic systems that extend the usefulness of blockchain applications.

Now that we’ve surveyed some examples, we can be more specific about how layer 2 solutions apply this insight. The economic mechanisms used by layer 2 solutions tend to be interactive games: they work by creating incentives for different parties to compete against or “check” one another. A blockchain application can assume that a given claim is likely true, because we’ve created a strong incentive for another party to provide information showing it to be false.

In state channels, this is how we confirm the final state of the channel — by giving parties a chance to “rebut” each other. In Plasma, it’s how we manage fraud-proofs and withdrawals. In Truebit, it’s how we ensure that solvers’ tell the truth — by giving an incentive to verifiers to prove the solver wrong.

These systems will help address some of the challenges involved in scaling ethereum to a massive global user base. Some, like state channels and Plasma, will increase the transaction throughput of the platform. Others, like Truebit, will make it possible to conduct more difficult computation as part of a smart contract, opening up new use cases.

These three examples represent only a small portion of the possible design space for cryptoeconomic scaling solutions. We’ve not even covered the work being done on “inter-blockchain protocols” like Cosmos or Polkadot (although whether these are “layer 2” solutions or something else altogether is a topic for another post). We should also expect to invent new and unexpected layer 2 systems that improve on existing models or offer new tradeoffs between speed, finality, and overhead.

More important than any particular layer 2 solution is further development of the underlying techniques and mechanisms that make them possible in the first place: cryptoeconomic design.

These layer 2 scaling solutions are a powerful argument for the long-term value of programmable blockchains like ethereum. Building the economic mechanisms underlying layer 2 solutions is only possible when a blockchain is programmable: you need a scripting language to write the programs that enforce the interactive games. This is much more difficult (or in some cases, like Plasma, probably impossible) on blockchains like bitcoin, which offer only limited scripting possibilities.

Ethereum lets us build layer 2 solutions to access new points on the tradeoff matrix between speed, finality, and overhead cost. This makes the underlying blockchain more useful for a larger variety of applications, since different types of applications with different threat models will have natural preferences towards different tradeoffs. For high value transactions where we want protection against even nation-states, we use the main chain. For trading digital collectibles where speed is more important, we can use Plasma. Layer 2 lets us make these tradeoffs without compromising the underlying blockchain, preserving decentralization and finality.

Further, it’s very hard to predict in advance what scripting capabilities will be needed for a given scaling solution. When ethereum was being designed, Plasma and Truebit had not yet been invented. But because ethereum is fully programmable, it is capable of implementing virtually any economic mechanism we can invent.

The only way to take full advantage of the value of blockchain technology — that core kernel of certainty created by cryptoeconomic consensus — is with a programmable blockchain like ethereum.

Thanks to Vitalik Buterin, Jon Choi, Matt Condon, Chris Dixon, Hudson Jameson, Denis Nazarov, and Jesse Walden for their comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Cover photo: Construction of the Tunkhannock Viaduct railway bridge in Pennsylvania (cc). Roman engineering principles being extended to new uses.